-40%

SUPER - Color Litho Travel Brochure Pamphlet- 1880 Natural Spring Bilina Bohemia

$ 105.07

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

SUPER - RARE - Advertising Travel Pamphlet / BrochureNatural Spring of Bilin

Bohemia

ca 1880

For offer - a very nice piece of ephemera! Fresh from an estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now.

Vintage, Old, antique, Original -

NOT

a Reproduction - Guaranteed !!

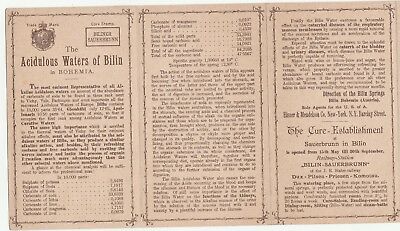

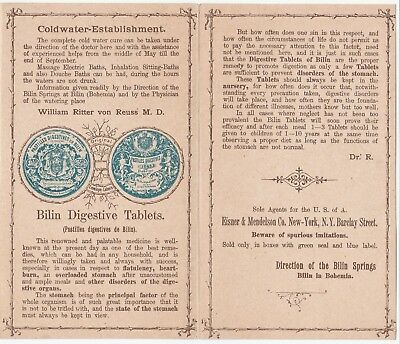

Very nice, rich high quality chromolithograph color graphic scenes including principal view, gardens, walkingway, etc. . Folds open to show different views. Renowned medicinal spring - Acidulous waters of Bilin, Bilin digestive tablets, cure-establishment at Sauerbrunn in Bilin - arrive at the railway station via J.R. States Railroad. Coldwater establishment, physician William Ritter von Ruess, M.D. Eisner & Mendelson Company, New York, sole agents in the United States. Chromolithographie printing by Willner & Fick / Sick / Lick - Teplitz, Bohemia.

In very good condition. Please see photos. If you collect travel, 19th century Eastern Europe / Austria / / history, American travel, advertisement ad, health resort, quack medicine,

etc., this is a nice one for your paper or ephemera collection.

Combine shipping on multiple bid wins!

1356

Bílina (Czech pronunciation: [ˈbiːlɪna]; German: Bilin) is a town in the Teplice District in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic. It is located on the river Bílina. It is known for its spas and as a source of the strongly mineralized water, Bílinská Kyselka (Biliner Sauerbrunn in German). From 1938 to 1945 it was one of the municipalities in Sudetenland.

Location[edit]

The historic town of Bílina lies in the valley of the river Bílina, between the Central Bohemian Massif and the Ore mountains. It is situated between two bigger cities: Teplice and Most.

To the south, the mountain Bořeň, resembles a lying lion.

History[edit]

The name of the town originates from the adjective white (bílý; bielý). The term Bielina symbolizes 'white', without any wood or the flowing river Běla.

The first written mention of the settlement (then a seat of a province) dates back to 993 and comes from the Chronicle of Bohemians, which describes a battle between Bretislaus I and the German emperor Henry III near the town.

Before the half of 13th century Ojíř of Friedberk built a new castle in the settlement, which was expanded into a town with bulwarks and three gates.

In the High Middle Ages German settlers were called into the border area of Bohemia, introducing German city law. Germans formed the vast majority, culture and history until their expulsion in 1945.

During 1420 the town of Bílina was kept by Albrecht of Koldice, well known for his anti-Hussite attitude. Thus, Bílina was surrounded and conquered by a Hussite Jakoubek of Vřesovice who returned the town of Bílina to the Koldice dynasty in 1436.

After 1502, the town of Bílina was owned by the House of Lobkowicz, to whom this town was returned to in 1989 during restorations.

Bílinská Kyselka mineral springs and Spa[edit]

In 1702 Princess Leonora of the House of Lobkowicz had the mineral spring cleaned and the very first spa guests began to visit. By the end of 19th century the spa Biliner Sauerbrunn (meaning "Carbonated springs from Bílina" in German) had become the pride of the town. Bílina also received the nickname "Vichy of Germany". The digestive pastilles produced here also provided a worldwide common name for digestive regulators and laxatives: "Seidlitz Powders." The lozenges were made from the spring's mineral water Sedlitz bitter water, which was also used in the local spa balneology.

Scientific descriptions of the medicinal properties of local water treatment have contributed to the works of significant balneologists, including Franz Ambrosius Reuss, August Emanuel von Reuss and Josef von Löschner. Father and son Reuss are in the spa Bílina memorial, which dominates the spa's central park.

In 1878 a large spa complex was built in a Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architect Franz Sablick. Thereafter the "Josephs Quelle" spring "temple" became popular, along with the Forest café, which was built as a timber pavilion in Swiss style.

2,225,000 bottles of Bílinská Kyselka mineral water were exported in 1889, the biggest importer being Germany.

Biliner Sauerbrunn, Franz Skopalik Wien 1899

Another turning point in the history of spa was a changeover in 1989, after the end of the Communist regime. The House of Lobkowicz regained a part of their original property, including the Spa of Bílinská Kyselka. The spa was later sold to a private company.

Places of interest[edit]

Chateau and the tower of town hall

Peace Square with SS Peter and Paul church in the background

Lobkovic château - built in the years 1675-1682 on the site of an earlier Gothic castle

Hussite bastion - a remnant of the massive town fortifications

Town Hall - an art nouveau building built at the beginning of the 20th century, is the town's pride.

Bílinská Kyselka Spa - a spa complex including the spring house of the mineral waters, cafes and natural amphitheater in a forest setting.

Bořeň - a large phonolite mountain, dominating the city and its surroundings.

St. Peter and Paul's church - an operational church and historic monument

Culture and Sport[edit]

The town boasts a modern stadium. In the new millennium a new ice-hockey hall was also built. The swimming pool dates from 1931.

Chromolithography is a unique method for making multi-colour prints. This type of colour printing stemmed from the process of lithography, and includes all types of lithography that are printed in colour.[1] When chromolithography is used to reproduce photographs, the term photochrome is frequently used. Lithographers sought to find a way to print on flat surfaces with the use of chemicals instead of raised relief or recessed intaglio techniques.[2]

Chromolithography became the most successful of several methods of colour printing developed by the 19th century; other methods were developed by printers such as Jacob Christoph Le Blon, George Baxter and Edmund Evans, and mostly relied on using several woodblocks with the colours. Hand-colouring also remained important; elements of the official British Ordnance Survey maps were coloured by hand by boys until 1875. The initial technique involved the use of multiple lithographic stones, one for each colour, and was still extremely expensive when done for the best quality results. Depending on the number of colours present, a chromolithograph could take even very skilled workers months to produce. However much cheaper prints could be produced by simplifying both the number of colours used, and the refinement of the detail in the image. Cheaper images, like advertisements, relied heavily on an initial black print (not always a lithograph), on which colours were then overprinted. To make an expensive reproduction print as what was once referred to as a “’chromo’”, a lithographer, with a finished painting in front of him, gradually created and corrected the many stones using proofs to look as much as possible like the painting in front of him, sometimes using dozens of layers.[3]

Process[edit]

Chromolithography is a chemical process. The process is based on the rejection of grease by water. The image is applied to stone, grained zinc or aluminium surfaces, with a grease-based crayon or ink. Limestone and zinc are two commonly used materials in the production of chromolithographs, as aluminium unfortunately corrodes easily. After the image is drawn onto one of these surfaces, the image is gummed-up with a gum arabic solution and weak nitric acid to desensitize the surface. Before printing, the image is proved before finally inking up the image with oil based transfer or printing ink. The inked image under pressure is transposed onto a sheet of paper using a flat-bed press. This describes the direct form of printing. The offset indirect method uses a rubber-covered cylinder that transfers the image from printing surface to the paper. Colours may be overprinted by using additional stones or plates to achieve a closer reproduction of the original. Accurate registration for multi-coloured work is achieved by the use of a key outline image and registration bars which are applied to each stone or plate before drawing the solid or tone image. Ben-Day medium uses a raised gelatin stipple image to give tone gradation. An air-brush sprays ink to give soft edges. These are just two methods used to achieve gradations of tone. The use of twelve overprinted colours would not be considered unusual. Each sheet of paper will therefore pass through the printing press as many times as there are colours in the final print. In order that each colour is placed in the right position, each stone or plate must be precisely ‘registered,’ or lined up, on the paper using a system of register marks.[2]

Chromolithographs are considered to be reproductions that are smaller than double demi, and are of finer quality than lithographic drawings which are concerned with large posters. Autolithographs are prints where the artist draws and perhaps prints his or her own limited number of reproductions. This is the true lithographic art form.[4]

Origins[edit]

Uncle Sam Supplying the World with Berry Brothers Hard Oil Finish, c. 1880. This cheaply produced chromolithographic advertisement employs a technique called stippling, with heavy reliance on the initial black line print.

Alois Senefelder, the inventor of lithography, introduced the subject of colored lithography in his 1818 Vollstaendiges Lehrbuch der Steindruckerey (A Complete Course of Lithography), where he told of his plans to print using colour and explained the colours he wished to be able to print someday.[5] Although Senefelder recorded plans for chromolithography, printers in other countries, such as France and England, were also trying to find a new way to print in colour. Godefroy Engelmann of Mulhouse in France was awarded a patent on chromolithography in July 1837,[5] but there are disputes over whether chromolithography was already in use before this date, as some sources say, pointing to areas of printing such as the production of playing cards.[5]

Arrival in the United States[edit]

1872 chromolithograph of roadside inn, published in Maryland

The first American chromolithograph—a portrait of Reverend F. W. P. Greenwood—was created by William Sharp in 1840.[6] Many of the chromolithographs were created and purchased in urban areas. The paintings were initially used as decoration in American parlours as well as for decoration within middle-class homes. They were prominent after the Civil War because of their low production costs and ability to be mass-produced, and because the methods allowed pictures to look more like hand-painted oil paintings.[7] Production costs were only low if the chromolithographs were cheaply produced, but top-quality chromos were costly to produce because of the necessary months of work and the thousands of dollars worth of equipment that had to be used.[8] Although chromos could be mass-produced, it took about three months to draw colours onto the stones and another five months to print a thousand copies. Chromolithographs became so popular in American culture that the era has been labeled as “chromo civilization”.[9] Over time, during the Victorian era, chromolithographs populated children's and fine arts publications, as well as advertising art, in trade cards, labels, and posters. They were also once used for advertisements, popular prints, and medical or scientific books.[10]

Opposition to chromolithography[edit]

Even though chromolithographs served many uses within society at the time, many were opposed to the idea of them because of their lack of authenticity. The new forms of art were sometimes tagged as "bad art" because of their deceptive qualities.[8] Some also felt that it could not serve as a form of art at all since it was too mechanical, and that the true spirit of a painter could never be captured in a printed version of a work.[8] Over time, chromos were made so cheaply that they could no longer be confused with original paintings. Since production costs were low, the fabrication of chromolithographs became more a business than the creation of art.

Famous printers[edit]

Louis Prang[edit]

A famous lithographer and publisher who strongly supported the production of chromolithographs was Louis Prang. Prang was a German-born entrepreneur who printed the first American Christmas card.[11] He felt that chromolithographs could look just as good as, if not better than, real paintings, and he published well-known chromolithographs based on popular paintings, including one by Eastman Johnson entitled The Barefoot Boy.[8] The reason Prang decided to take on the challenge of producing chromolithographs, despite criticisms, was because he felt quality art should not be limited to the elite.[11] Prang and others who continued to produce chromolithographs were sometimes looked down upon because of the fear that chromolithographs could undermine human abilities. With the Industrial Revolution already under way, this fear was not something new to Americans at the time. Many artists themselves anticipated the lack of desire for original artwork since many became accustomed to chromolithographs.[8] As a way to make more sales, some artists had a few paintings made into chromolithographs so that people in society would at least be familiar with the painter. Once people in society were familiar with the artist, they were more likely to want to pay for an original work.[8]

Lothar Meggendorfer[edit]

German chromolithographers, largely based in Bavaria, came to dominate the trade with their low-cost high-volume productions. Of these printers, Lothar Meggendorfer garnered international fame for his children's educational books and games. Owing to political unrest in mid-19th century Germany, many Bavarian printers emigrated to the United Kingdom and the United States, and Germany's monopoly on chromolithographic printing dissipated.

August Hoen[edit]

A. Hoen & Co., led by German immigrant August Hoen, were a prominent lithography house now known primarily for its stunning E.T. Paull sheet music covers. They also made advertisements, maps, and cigar box art. Hoen and his brothers Henry and Ernest took over the E. Weber Company in the mid-1850s upon Edward Weber's death. August Hoen's son Alfred ran the firm from 1886 throughout the early 20th century.[12]

Rufus Bliss[edit]

Rufus Bliss founded R. Bliss Mfg. Co., which was located in Pawtucket, Rhode Island from 1832 to 1914. The Bliss company is best known for their highly sought after paper litho on wood dollhouses. They also made many other lithoed toys, including boats, trains, and building blocks.[13]

M. & N. Hanhart[edit]

Established in Mulhouse in 1830 by Michael Hanhart who initially worked with Godefroy Engelmann in London. The firm, established at Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square, was named after his two sons Michael and Nicholas. Artists like Joseph Wolf, Joseph Smit, J G Keulemans and others worked for him to produce natural history illustrations that were used in the Ibis (1859-1874), Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (1848-1900) and a range of books. The company wound up in 1902 after the death of Nicholas Hanhart and the rise of new printing techniques.[14]

Uses[edit]

"Love or Duty", a chromolithograph by Gabriele Castagnola, 1873

Chromolithographs are mainly used today as fine art instead of advertisements, and they are hard to find because of poor preservation and cheaper forms of printing replaced it. Many chromolithographs have deteriorated because of the acidic frames surrounding them.[15] As stated earlier, production costs of chromolithographs were low, but efforts were still being made to find a cheaper way to mass-produce colored prints. Although purchasing a chromolithograph may have been cheaper than purchasing a painting, it was still expensive in comparison to other colour printing methods which were later developed. Offset printing replaced chromolithography in the late 1930s.

To find or purchase a lithograph, some suggest searching for examples with the original frame as well as the publisher's stamp.[16] Both European and American chromolithographs can still be found, and can range in cost from hundreds to thousands of dollars. The least expensive chromos tend to be European or produced by publishers who are less well-known compared to Prang.[16]

Bibliography[edit]

Twyman, Michael. A History of Chromolithography: Printed Colour for All. The British Library/Oak Knoll Press, 2013.

Friedman, Joan M. Colour Printing in England, 1486-1859. Yale Center for British Art, 1978.

Henker, Michael. Von Senefelder zu Daumier: Die Anfange der Lithograpischen Kunst. K.G. Saur, 1988.

Jay, Robert. The Trade Card in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Missouri Press, 1987.

Last, Jay T. The Colour Explosion: Nineteenth-Century American Lithography. Hillcrest Press, 2005.

Marzio, Peter C. The Democratic Art : Pictures for a 19th-century America : Chromolithography, 1840-1900. D. R. Godine, 1979.

Further reading[edit]

Friedman, Joan M. Colour Printing in England, 1486-1870: an Exhibition, Yale Center for British Art. New Haven: The Center, 1978.

Hunter, Mel. The New Lithography: A Complete Guide for Artists and Printers in the Use of Modern Translucent Materials for the Creation of Hand-Drawn Original Fine-Art Lithographic Prints. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1984.

Marzio, Peter C. "Lithography as Democratic Art: A Reappraisal." Leonardo 3(1971):37-48.

See also[edit]

Look up chromolithography in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Planography

Photochrom

Color printing

Zincography

History of graphic design

Lithography